As an historical post-script the following text has been adapted from the Pitkin Guide to D-Day and Derek Woods’s history of the ROC “Attack Warning Red” - Editor

After the dramatic evacuation from Dunkirk in 1941 Winston Churchill set up the Combined Operations Staff to undertake the preparation for the invasion of Europe. Three years later this turned out to be an undertaking without precedent for complexity and co-ordination in the history of warfare.

The failure of the Allies’ raid on Dieppe in August 1942 wrongly convinced the Germans that massive coastal defences were the answer to invasion. They pressed ahead with the building of the Atlantic Wall, a series of mighty concrete batteries and beach obstacles that was intended to stretch from the Low Countries to Brittany.

The capability to ship supplies of food, munitions, equipment and reinforcements to the Allied invaders was crucial, but a frontal attack on a suitable port like Dieppe was clearly suicide. From this grew the determination to ‘take the port with us’ - to build artificial harbours, and to by-pass fixed defensive installations. The selection of the invasion site was fundamental to success, and the Pas de Calais was obviously attractive, with a narrow sea crossing, direct access to the heartland of Germany and close to airfields in England. Here the Germans created the most formidable defences, and it was here that the Allies’ deceived the Germans into thinking a huge army stood ready in south-east England and kept half the German forces awaiting the ‘real’ invasion for weeks after D-Day.

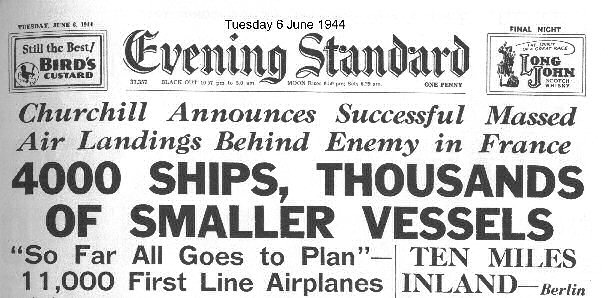

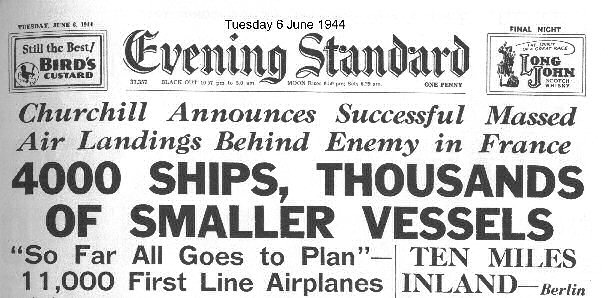

All over England the forces gathered under the Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower. 20 American divisions, 14 British, three Canadian and one each from Poland and France, with nearly 8,000 aircraft, over 4,000 landing craft and ships and nearly 300 fighting vessels; 2,876,439 men in total.

General Montgomery’s plan for Operation OVERLORD was to secure the eastern flank along the Orne, including Caen and Falaise, using British, Canadian, French and Polish troops. Meanwhile, in the west, the American forces of Lt General Omar Bradley would take the Cotentin peninsula, freeing Cherbourg to act as a supply harbour, then thrust south to the Loire to create a north-south front, before the whole force rolled eastwards towards Paris and the Seine.

For the ROC all this was only of passing interest, as they concentrated on reporting the mass of Allied aircraft which daily filled the sky. Behind the scenes, however, moves were afoot to give the ROC a vital part to play in “Operation Overlord”. On March 11, 1944, the Commander-in-Chief AEAF, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, issued a request for some 2,000 experienced ROC personnel to act as aircraft spotters on defensively equipped merchant ships (DEMS). The authorities were concerned that aircraft recognition standards were almost non existent on most of these ships and unless some experts could be made available there was every likelihood of enemy aircraft passing unrecognised and friendly forces being hit by anti-aircraft fire.

At a conference held on April 5, 1944 it was agreed that 240 men in pairs could be taken aboard 30 British LSI’s (Landing Ships Infantry) and 90 MT’s (Motor Transport) ships, while the United States would need 300 men or more. The ROC being a civilian body and largely immobile, it was decided to enlist volunteers into the Royal Navy with the equivalent rank of Petty Officer for one month with the option of extension to two months if need be. Personnel were to continue to wear ROC uniform with the addition of a shoulder badge bearing the word “Seaborne.” Members were to be paid a special rate of 1/- a day.

On April 28 Air Ministry issued a confidential order entitled “Special Scheme for Royal Observer Corps Participation in Forthcoming Operations” outlining details of the plan. At the same time Air Commodore Finlay Crerar sent the following letter to every post member of the Corps:

| “I write this message to each of you in every post in the United Kingdom

and I want you to read it carefully; I want each of you to consider carefully

your own position and make up your mind which path yours must be at this most

important crossroads. Much depends on your decision. Many of you have asked me from time to time whether you could have the chance of taking part in more active operations, and I believe many of you who have for so long been on the defensive will welcome tile chance to join in the offensive. I can tell you now of what is not only the most important operational requirement but a handsome and well deserved tribute to the skill and value of the corps to the fighting services. The supreme command has asked me to provide a considerable number of ROC observers to serve on board ship for recognition duties during forthcoming operations. The highest importance is attached to this request, for inefficient and faulty recognition has contributed largely to enemy successes against our shipping and to losses of aircraft from friendly fire. This request is one which demands the best which the Corps can give; it calls for skill in instant recognition, readiness to share the hardships of the fighting services in amphibious operations and personal sacrifice on the part of those members left behind who must carry on . . . No other organisation possesses our skill and experience in aircraft recognition. Our invasion forces need something which we have got. We cannot fail to give it, and give it now.” |

No fewer than 1,376 observers (701 “A” and 646 “B” men) volunteered, together with 29 officers. Of these 1,094 reported to the reception in Bournemouth. Subsequently 81 were turned down on medical grounds, 209 failed to qualify in the very tough trade test and eight withdrew at their own request. The remaining 796 were enrolled in the Royal Navy. Of the rejected volunteers, 68 agreed to accept posting to one of the south coast posts to replace observers in the forward zone.

Volunteers came in every shape and size aged from 17 to 70. The youngest was 17 year old Observer Ian Ramsbotham of Woolaston School, Stoke-on-Trent. He had gained a Spitfire badge in the 1943 master test and could recognise anything that flew. When his service was finished “Petty Officer” Ramsbotham accepted his honourable discharge and went back to school. For the older Class “B” post personnel it usually meant telling their employers they would be away for a month or two, packing a bag and bidding the amazed wife and family goodbye. Only the ROC could take a man who had fought in khaki in the trenches of the First World War, give him an RAF blue uniform for his service in the Second World War and then turn him into an equivalent Petty Officer in the Royal Navy!

The reception had a permanent staff of ROC RN and RAF officers under the command of Observer Commander Cooke of No 11 Group, ROC. The volunteers were subjected to a medical and a stiff aircraft recognition trade test. Those accepted were put through a further intensive course in aircraft recognition and in elementary naval procedures. Initially the recognition test took the form of a film, and one volunteer from the Scottish highlands remarked that it was the first “movie” he had ever seen. To give live practice in picking out hostiles the RAF’s flying circus of captured German aircraft laid on fly-pasts. Further naval training was given at HMS Safeguard, a land ship in the New Forest. Observers were given the equivalent petty officer rank of Aircraft Identifier and kitted out with RN arm-badges, Sou’westers, tin hats, life jackets, sun glasses, rubber boots, etc.

The whole scheme was put together in a remarkably short time and the effect on the Corps as a whole was most marked. Observers from every corner of the land, normally used to the closed environment of a particular post or centre crew, were suddenly flung together for eating, sleeping and working. The barriers of geographical area or of Group disappeared and the unity of purpose, thus established, was to be carried on through the annual camps of post-war years. By May 15, 1944, just 16 days after the promulgation of the seaborne scheme, the first observers had been drafted away to their ships. By D-Day on June 6 almost 500 were on board ship; by June 13 this was up to 700.

Many had had hair-raising experiences; two were killed by enemy action, 22 survived their ships being sunk, one was injured by shell splinters and one was injured by a flying bomb when his ship was in dock. The members killed were observer J. B. B. Bancroft (MV Derry Cunihy) and observer W. J. Salter (SS Empire Broadsword).

Messages began to flow in from ships; captains, naval authorities and air commanders - all were unanimous in their praise of the work of the ROC. Special messages of congratulation came in from Admiral Ramsay, Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief, and from Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, the Air Commander-in-Chief AEAF.

| (aircraft identifiers W. E. Hills and J. F. Rolski),

Lieutenant Lyon, commanding US Naval armed guard aboard the ship, wrote to

the Commandant, 19 Group: “ Subject named men, formerly members of your command, and now serving as aircraft identifiers on our ship, Merchant Transport 22, attached to my US Naval gun crew, have already proved their weight in gold to us in properly and quickly identifying all aircraft we have encountered in our initial invasion trip. As an example, on the morning of June 10th, with visibility poor, they caused us to hold our fire on two RAF Spitfires which all other ships, except naval units, were firing at for a period of a half hour. When they reported aboard they told me they could identify anything which they could see. Such has proved to be the case and I find myself, along with my men, relying on them for services far in excess of any other personnel in the crew. It is a pleasure to have them with us, and a great satisfaction to have men so carefully trained to do a job which is so important for the safety of our troops and our cargo”. |

| “ It appears that this vessel has been credited with the MeI09 which burst into flames ... The Master speaks most highly of the behaviour of his DEMS and ROC ratings. Aircraft Identifier J.Devlin identified the Me109’s at the commencement of the attack, while on another occasion aircraft identifier C. S. Reddihough identified a flight of Spitfires and gave a timely warning to the gun crew. The employment of aircraft identifiers in this vessel was therefore fully justified.” |

| “ The general impression amongst the Spitfire wings covering our land and naval forces over and off the beach-head appears to be that in the majority of cases the fire has come from naval warships and not from merchant ships. Indeed I personally have yet to hear a pilot report that a merchant vessel had opened fire on him.” |

| “

I must say I felt very proud of them and the way they were doing their job.

They are giving instruction in aircraft recognition to the US gunners and were

getting a test ready. . . Naturally, the gunnery officers of DEMS and US armed

guard officers were sometimes sceptical at first, but now they and the ships’ Masters

are delighted with the venture and the difficulty is going to be to get them

to part with the observers who have completed their time. The officers feel

far less worried now that they have expert opinion on identification and as

they have learnt from experience that the ROC are correct they rely implicitly

on their statements Our men have had complete control over gun crews and not a shot has been fired at our own aircraft in daylight. It should be added that this is in spite of intense fire directed against our own aircraft from the shore and the light landing craft coming to and from the beaches. Two observers reported to me today that they had identified at different times two Me 110’s, two FW 190’s and a third FW 190 immediately on being sighted, which was the direct cause of the first four aircraft being shot down and possibly the fifth . . . I asked one American officer his opinion of our observers and he replied that they had prevented the gun crews from shooting down two of their own Thunderbolts, which speaks for itself. .” |

The ROC efforts during the invasion proved so effective that the AEAF made recommendations for all ships in the invasion fleet to have aircraft identifiers. That the Admiralty should establish a new trade of aircraft identifier and that ROC personnel could be used as instructors. The War Office, at the instigation of 21 Army Group, also wanted help from the ROC and approached the Air Ministry with a view to obtaining the services of some 100 ROC personnel. These were to be stationed near the Mulberry-harbour site on the beaches and were to fire signal flares to stop AA fire at friendly aircraft. The War Office letter on the subject was dated August 4, 1944, and it contained one telling paragraph:

| “The responsibility is a heavy one and calls for greater expert aircraft recognition than can be provided by the Army, including personnel of Anti-Aircraft Command.” |

However with the rapid advance of the Allied Armies it was decided that the provision of 100 observers for the beaches would not be necessary

The sequel to the ROC’s efforts during the invasion came in October 1944 when the Permanent Under Secretary wrote to Air Commodore Finlay- Crerar:-

| “I am commanded by the Air Council to inform you that

they have received from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty an

expression of their appreciation of the services rendered by seaborne

volunteers of the Royal Observer Corps who served in the Royal Navy as

aircraft identifiers during the invasion of France.

I am also to inform you that in recognition of their services His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to approve the wearing of the shoulder badge ‘Seaborne’ as a permanent part of their uniform by all who took part in this operation and were honourably discharged from the Royal Navy on completion of their contract, or on medical grounds at an earlier date. The Air Council have learned with satisfaction that as a token of the good work of those members of the Royal Observer Corps who temporarily joined the Royal Navy as aircraft identifiers: Observer Lieutenant George Alfred Donovan Bourne, Leading Observer Joseph Douglas Witham and Observers Thomas Henry Bodhill, John Hughes, Derek Norman James, Edward Jones, Albert Edward Llewellyn, George McAllan, Anthony William Priestly and John Weston Reynolds have been mentioned in despatches.” |

And from the Air Commander-in-Chief AEF Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory:-

| “I have read the reports from both pilots and naval officers regarding the Seaborne volunteers on board merchant ships during the recent operations. All reports agree that the Seaborne volunteers have more than fulfilled their duties and have undoubtedly saved many of our aircraft from being engaged by Seaborne Service ships’ guns. I should be grateful if you would please convey to all ranks of the Royal Observer Corps, and in particular to the Seaborne volunteers themselves, how grateful, I and all the pilots in the Allied Expeditionary Air Force are for their assistance, which has contributed in no small measure to the safety of our own aircraft, and also to the efficient protection of the ships at sea. The work of the Royal Observer Corps is often quite unjustly overlooked and receives little recognition, and I therefore wish that the service they have rendered on this occasion be as widely advertised as possible and all Units of the Air Defence of Great Britain are therefore to be informed of the success of this latest venture of the Royal Observer Corps” |